Physical Therapy Videos - Forearm

What Is It?

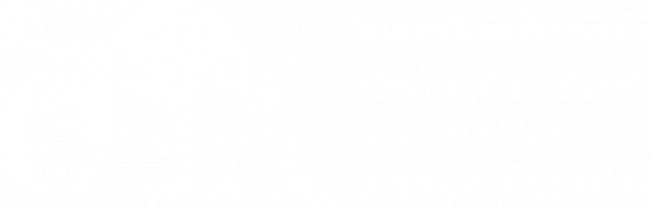

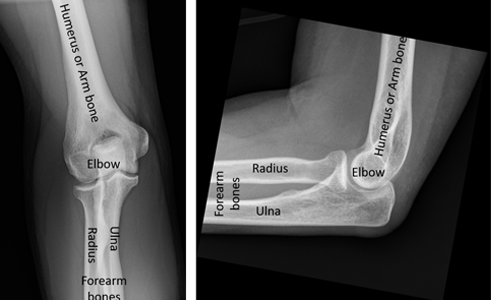

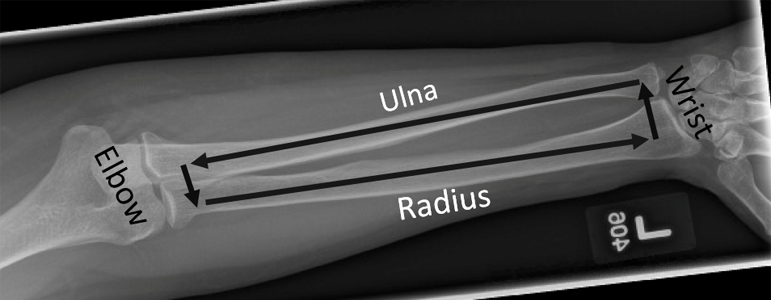

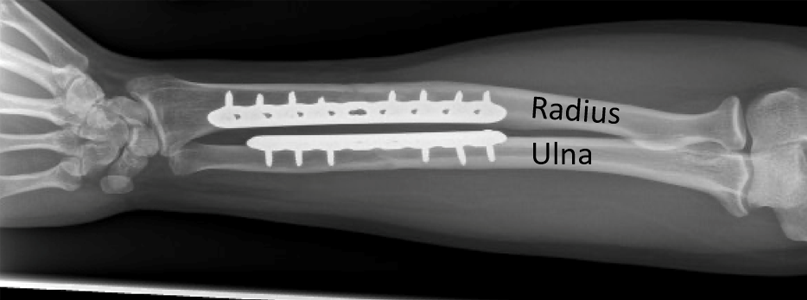

The arm has two long bones, the radius and the ulna. They go from the elbow to the wrist. The ulna is straight, but the radius is curved. This shape lets the radius twist around the ulna. This lets you turn your hand up or down.

The radius and ulna are joined by two "radioulnar" joints, making a ring shape. A strong band of tissue (not seen in the X-rays) connects them along the arm. This is called the interosseous membrane.

Many long muscles cover the radius and ulna. They help move your wrist, hand, and fingers. Arteries and nerves also go through your arm. They give blood and feeling to your hand and arm. These nerves also help control muscles, so you can use your hand and fingers.

How It Happens

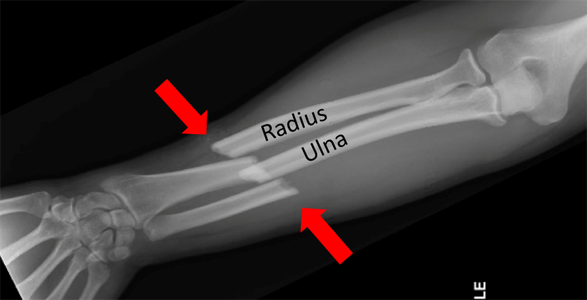

The arm bones can break from a direct hit to the arm or a fall onto the outstretched hand. Because the radius and ulna are connected like a ring, breaks usually happen in two places. Often, both the radius and ulna break. This is called a "both bone" forearm fracture.

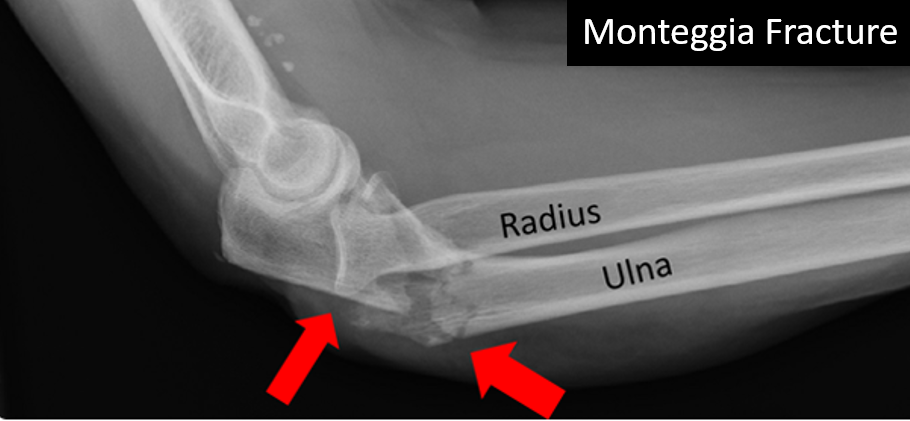

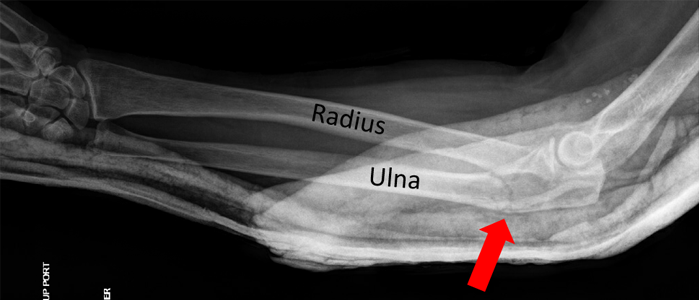

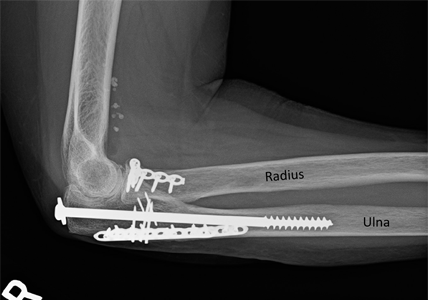

Sometimes only one bone breaks. This might mean a joint is out of place. These injuries are called a Galeazzi fracture (radius fracture and joint sprain at the wrist) or a Monteggia fracture (ulna fracture and joint sprain at the elbow).

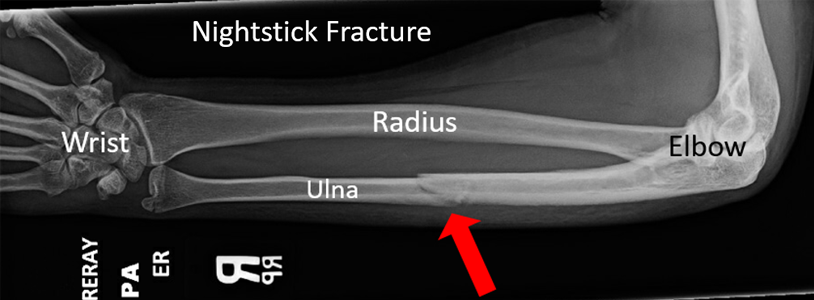

Once in a while, one bone breaks by itself without other injuries. This usually happens after a direct hit to the middle of the arm, and is sometimes called a "nightstick injury" (named from long ago when someone was hit with a club or stick).

First Steps

Arm fractures are very painful. The arm might look bent or deformed. It may be hard to move your fingers or wrist. A doctor will use an x-ray to see where your arm is broken. They might place a splint or cast to keep your arm still and in a better position. If bones poke through the skin, this is called an open (compound) fracture. It needs fast treatment to prevent infection. You will likely get a tetanus shot, antibiotics, and surgery to clean the wound.

Treatment

In adults, radius and ulna fractures usually need surgery. Because these bones roll and glide over each other, it is important to fix their shape and position. It can be hard to hold them in place with just a cast or splint. In young kids, arm fractures are often treated with a cast, and only sometimes need surgery. Surgery means making cuts on the arm to reach the bones. This can be one or more cuts. Most often the surgeon uses plates and screws to hold the bones in place.

If your bone poked through the skin, the surgeon will clean the wound and bone to remove any dirt or bad tissue. In rare cases, muscles in your arm can swell because of the fracture. If the swelling is really bad, it can affect blood flow in your arm. This is called compartment syndrome. Bad pain that gets worse is the most common sign of compartment syndrome. Tell your doctor right away if your pain is getting worse. Compartment syndrome can happen before, during, or after surgery, and needs fast treatment.

If only one bone is broken and the bone hasn't moved out of its normal place, your doctor might decide to treat you with just a cast instead of surgery. After surgery, you may need to wear a splint. You might not be able to lift much, but it's important to move your fingers to avoid stiffness and help reduce swelling. Your surgeon will give you instructions on how to move your arm after surgery. It's very important to follow your doctor's instructions.

Long Term

If the arm bones heal with their normal shape, long-term function is usually good. Often, the metal plates and screws can stay inside your arm forever. However, if they bother you, they may need to be removed after the bones have healed. For injuries that involve the joints, you may have some stiffness in the elbow or wrist. In rare cases, one of your bones may not heal (non-union), or there may be another problem like an infection that needs more surgery.

Physical Therapy Videos - Forearm

---

Geoffrey Wilkin, MD

Edited by the OTA Patient Education Committee and Steven Papp, MD (section lead)

X rays and images from the personal collection of Dr Wilkin and Christopher Domes, MD